Commissioned By

Additional Funding

Collaborators

Methodologies

Forums

Exhibitions

On 19 December 2023, FA and Al-Haq published a new analysis of the condition of the archaeological site in the area of Gaza’s Al-Shati refugee camp, in light of the Israeli military offensive since October 2023.

Our new findings, below, connect Israel’s destruction of Palestinian cultural heritage to the environmental damage caused by pumping seawater into Gaza’s aquifer, which could constitute ‘evidence of Israeli officials and military’s intent to erase and destroy the Palestinian people in Gaza’, according to a new report by Al-Haq.

Along the coastline of the Gaza Strip, beneath layers of rubble, lies one of Palestine’s hidden treasures and one of the region’s most important archaeological sites. Repeated bombings, and the humanitarian disaster inflicted on Palestinian communities by the decades-long Israeli occupation and siege, as well as advancing coastal erosion and necessary development within the enforced densification of Gaza, have placed this unique site under existential threat.

‘Targeting cultural heritage is not an empty gesture. Culture constitutes a visible expression of human identity. Depriving a people of their culture is tantamount to emptying them of the very substance that forms the backbone of their right to self-determination, especially in a context of cumulative, interconnected and systemic human rights violations.’ –Al-Haq

The Site

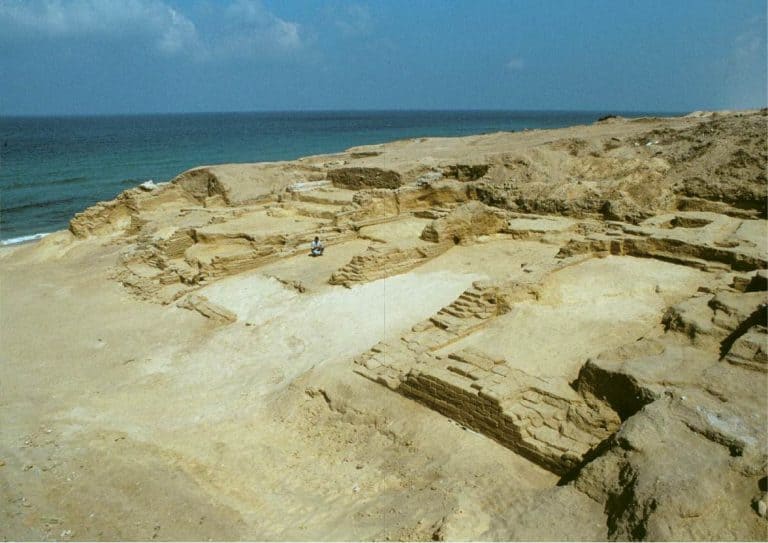

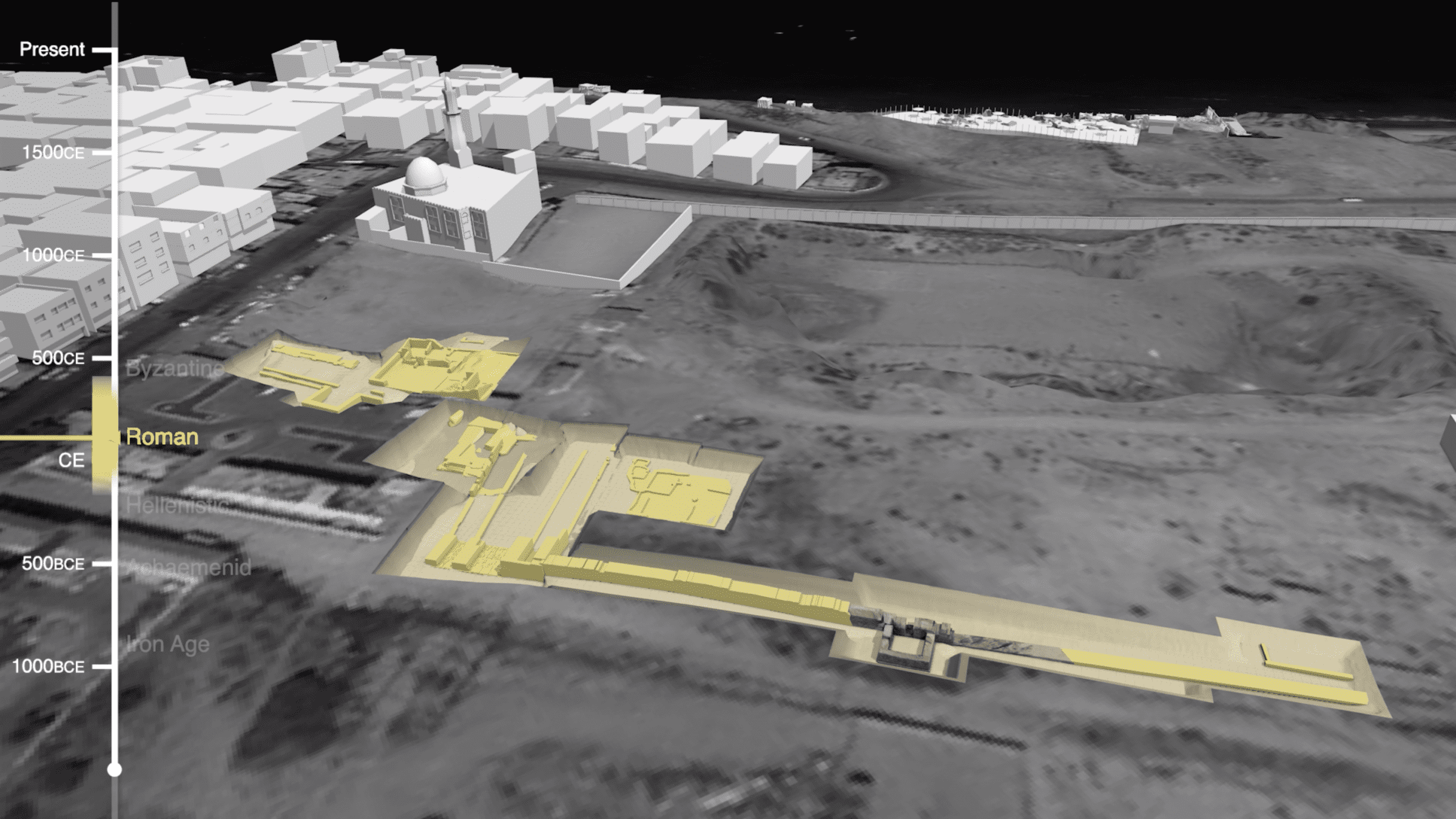

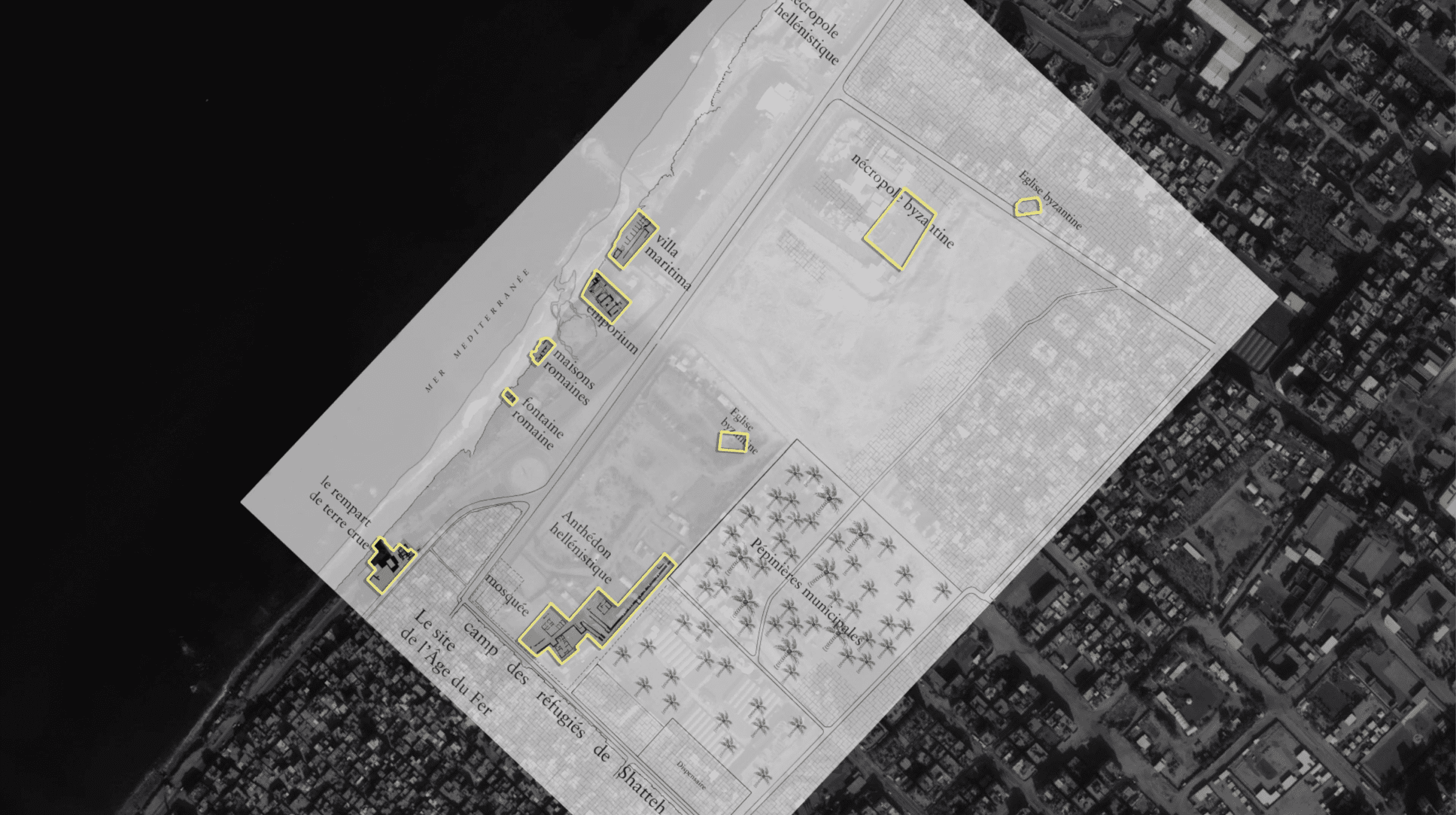

The site includes a series of excavations undertaken from 1995-2005, extending from an Iron Age rampart (a defensive wall) underneath Achaemenid period houses (fig. 2), to Roman and Hellenistic-era structures including an emporium (fig. 3) and tiled fountain on the coast, to a Byzantine cemetery in the north (fig. 4). 1

Inland, archaeologists unearthed extraordinary findings from the Greco-Roman period, including the Roman city wall and villas, and Hellenistic-era houses whose painted decorations illustrate influences from across the Mediterranean (fig. 5). These finds formed part of the city of Anthedon, one of the most important Hellenistic-era ports on the Mediterranean.

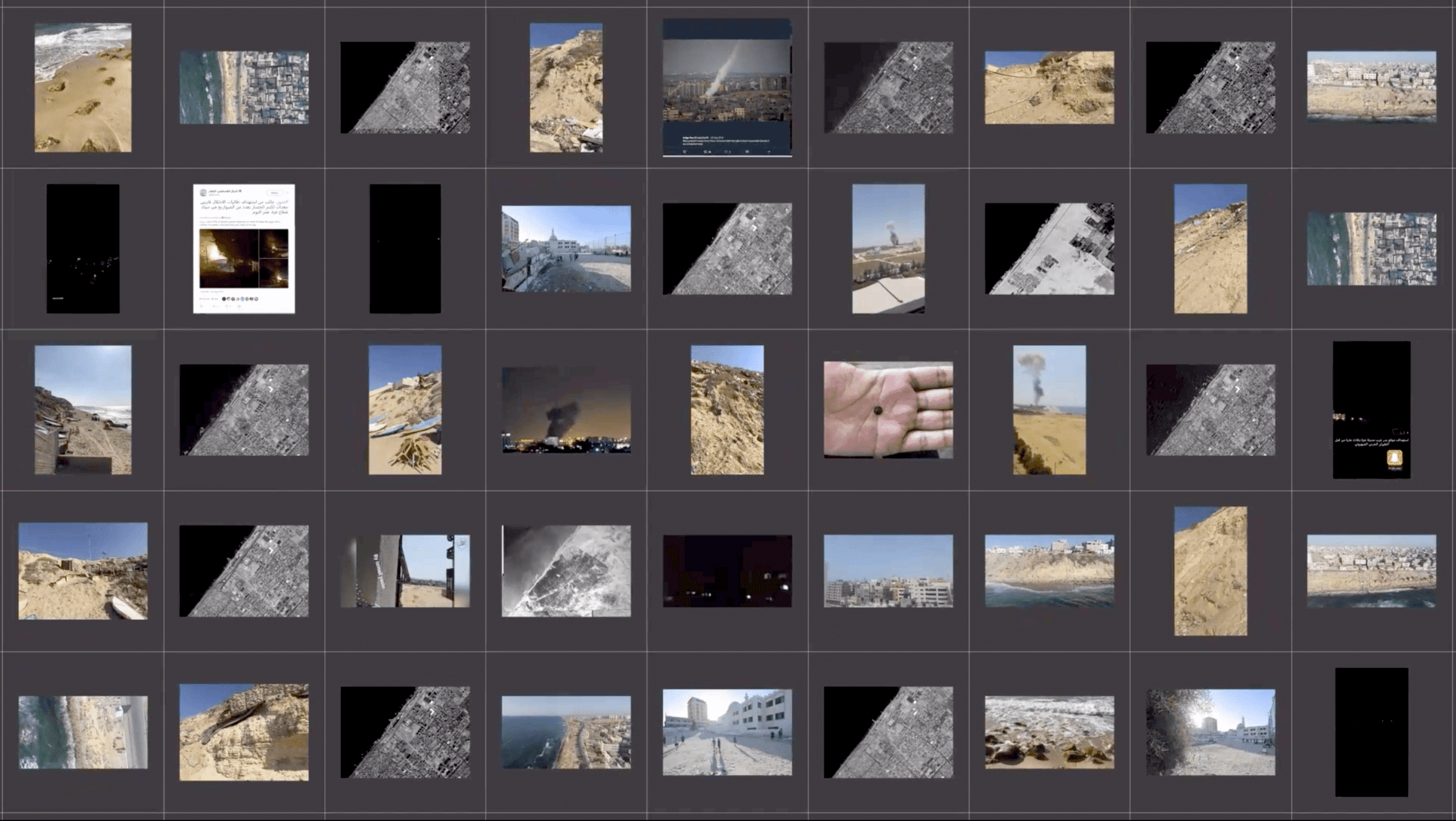

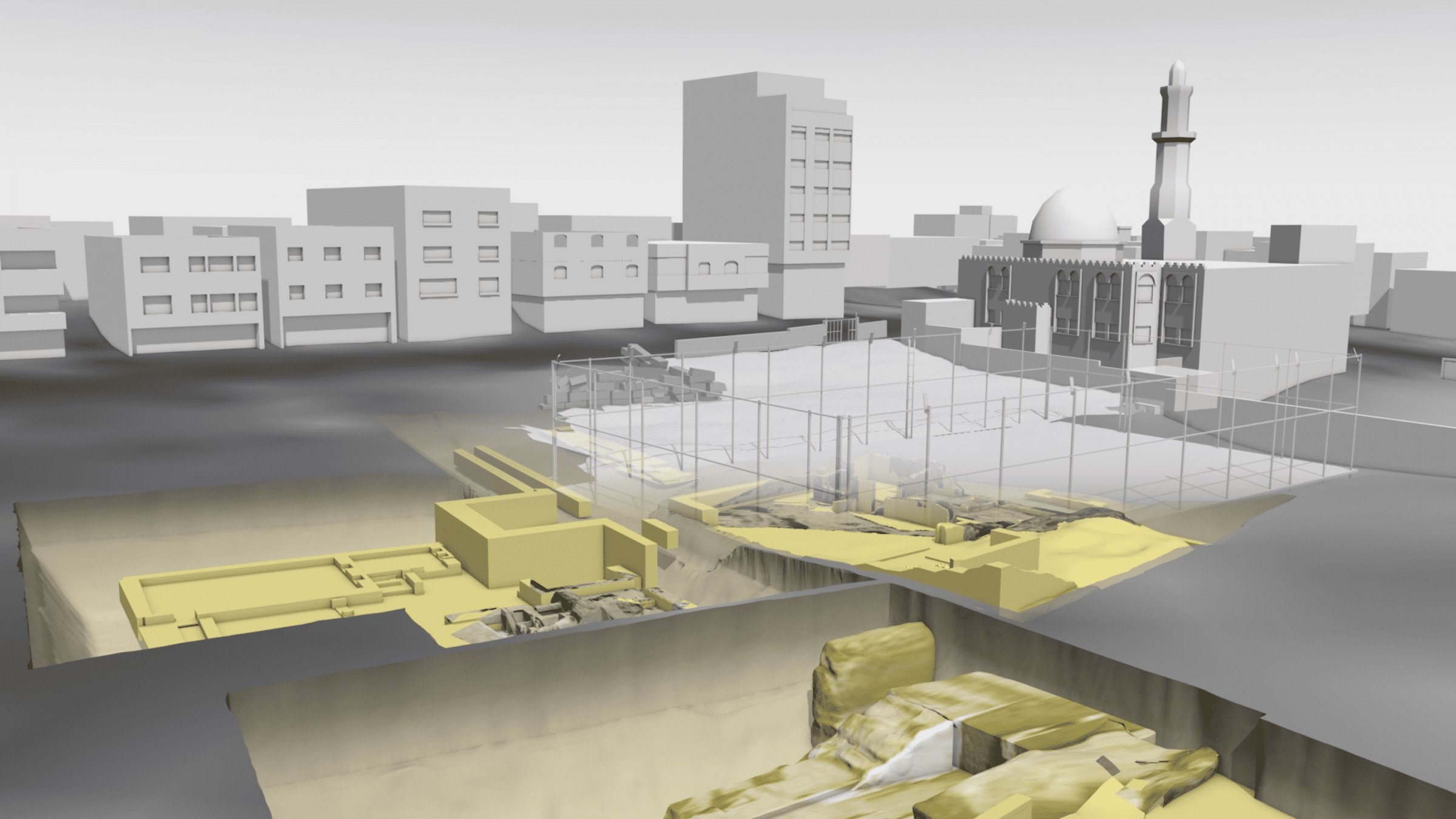

In collaboration with journalists in Gaza and abroad, residents, and archaeologists, Forensic Architecture (FA) collected, verified, and located hundreds of pieces of evidence about the site, and used 3D modelling and image mapping technologies to reconstruct its ongoing transformation, in what is a pioneering example of the application of open source visual investigation techniques to a site of archaeological interest.

Archaeology as a tool for open-source investigation

Archaeology in Palestine has deep colonial roots. Colonial archaeology prioritises certain periods of interest and rarefies them, while the findings of biblical archaeology in particular have been used for centuries to displace, exploit, and erase cultures living on the surface. 2 The practice and deployment of archaeology has thus tended to be disconnected from the daily realities within which it is located, to disregard local knowledge and to silence the lived experience around or above it. 3 By this same token, heritage preservation has often sanitised and decontextualised the very sites and objects it aims to protect.

In recent decades, archaeological sites surrounding Palestinian communities have been disregarded, or worse, destroyed by Israeli occupation forces. 4 While historic sites in Gaza such as Anthedon have been erased, others outside of the besieged enclave, such as Caesarea or Apollonia-Arsuf, are being actively preserved and promoted (figs. 6 and 7). This disregard for and destruction of Palestinian cultural heritage both diminishes Palestinian claims to statehood and denies Palestinians their fundamental right to access and preserve their own heritage. 5,6

This project is the first in which FA has undertaken archaeology. Our aspiration with this project was to take a first step towards bringing the practice and methods of archaeology into contact with open source investigation, its ethos of collaboration and its integration of local expertise. This approach can be used not only to study and protect the past, but to connect it to the present and thus contest ongoing forms of colonial domination and state violence.

Israeli offensive on Gaza, May 2021

In May 2021, Israeli occupation forces conducted yet another massive bombardment of the Gaza Strip, killing more than 250 Palestinians*, including 66 children. 7 The bombing toppled high-rise buildings, destroyed major roads and commercial areas, and hit essential infrastructure, including hospitals and schools.

The bombs also impacted important cultural and archaeological sites. Colleagues in Gaza told us about bombs which have fallen within the known perimeter of this archaeological site, inland and along the coastline. We found evidence of bomb craters (fig. 8) directly above buried archaeological remnants; even as international law, under certain conditions, dictates that such attacks against historic monuments may amount to war crimes. 8

The Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), which is now investigating the ‘Situation in the State of Palestine’ 9, wrote that ‘attacks on cultural heritage may violate not only international humanitarian law but human rights as well.’ 10 In their legal report Cultural Apartheid: Israel’s Erasure of Palestinian Heritage in Gaza, based in part on our findings, Palestinian human rights group Al-Haq argues that ‘Israel’s bombardments [in Gaza] not only breach the principle of military necessity in violation of the laws of armed conflict, but also aim at gradually erasing Palestinian cultural heritage to deny the Palestinian people of their right to self-determination over their cultural resources, and by extension threatens their existence as a people. Such bombings are a gross violation of the Rome Statute [of the ICC], constituting war crimes, and crimes against humanity.’ 11

The contents of this report, which includes the main findings from our investigation, will be submitted as evidence to the ICC and OHCHR.

*In the voiceover to our video investigation, we stated that Israeli strikes in May 2021 killed 247 Palestinians, however, the total death toll according to OCHA was 256.

Site history

The story of the excavation of this site began in 1995 during the ‘Oslo Process’, which sought the establishment of a measure of self-government in Palestine, buoyed by the return of thousands of Palestinians who had been living in exile. Part of the agreements involved the establishment of bureaucratic structures needed for Palestinian statehood, including a Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities responsible for the promotion and preservation of national heritage.

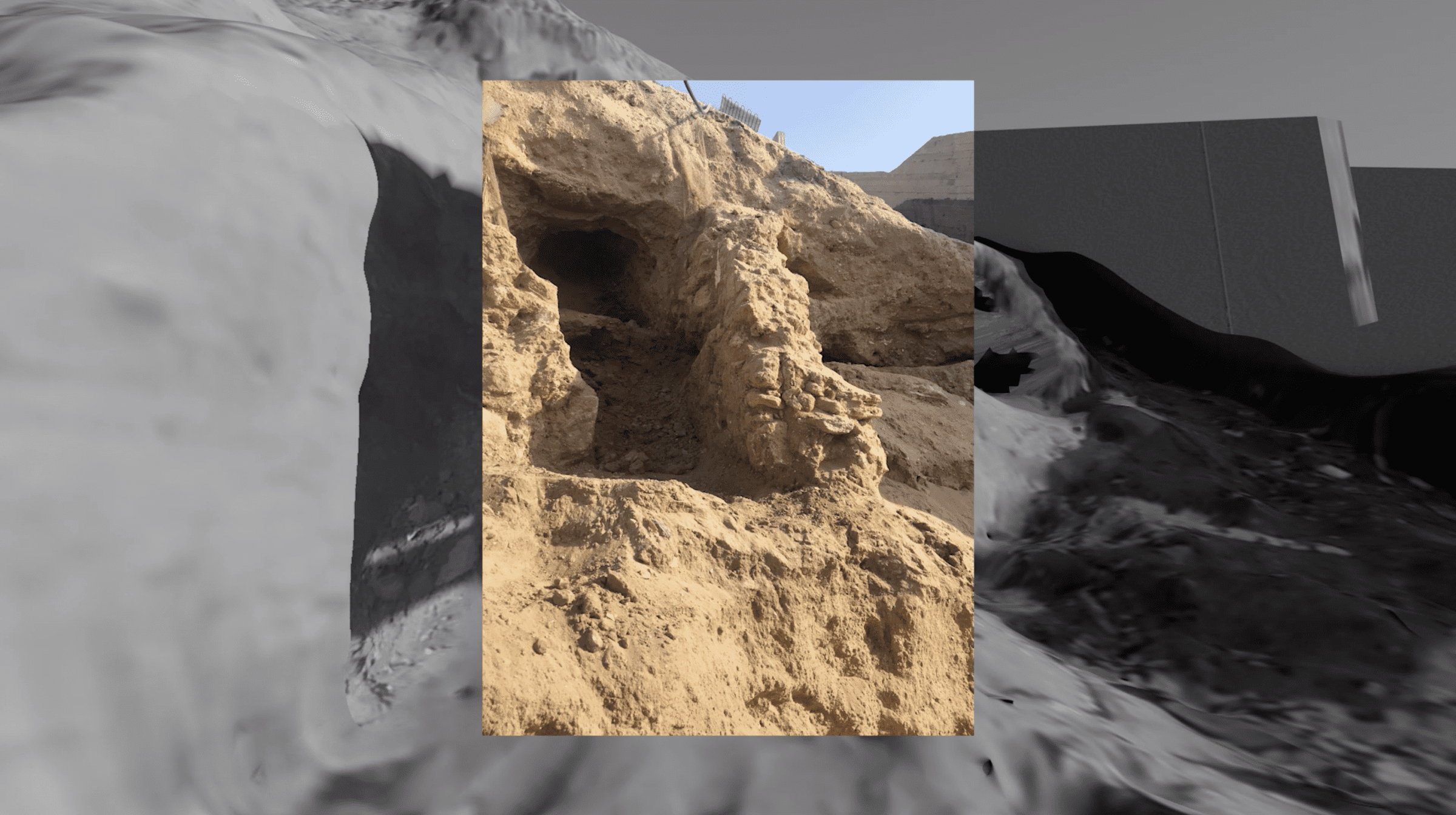

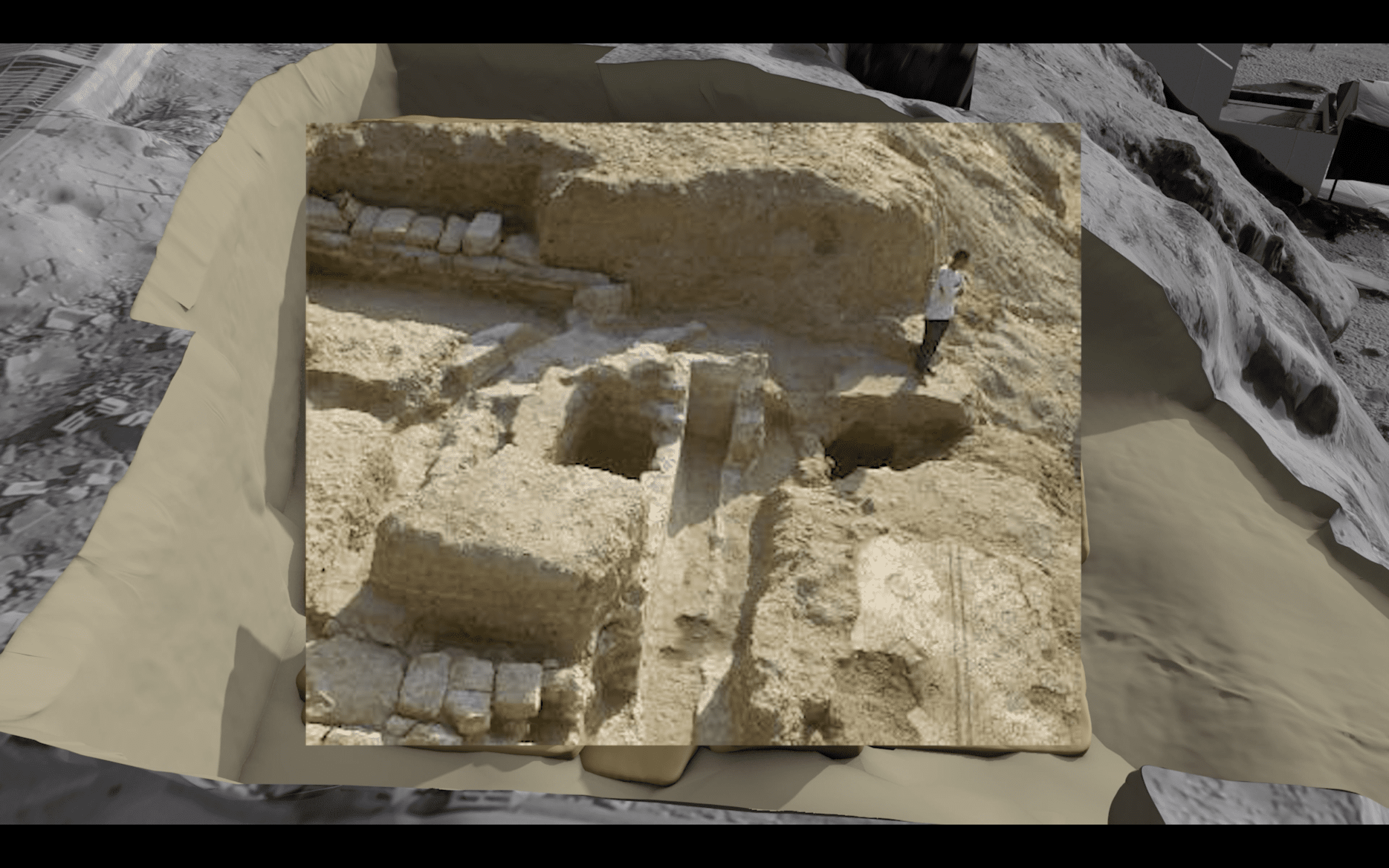

Collaboration between Palestinian and international archaeological teams facilitated a number of excavations (fig. 1), one of which was a French-Palestinian cooperation led by Professor Jean-Baptiste Humbert of the École Biblique et Archéologique Française de Jérusalem (French Biblical and Archaeological School of Jerusalem). When Humbert and his team arrived in the area in 1995, Palestinian children from the adjacent al-Shati refugee camp showed them these ruins (fig. 9) of a Roman fountain along the coastline, where they consequently began to excavate. 12

Further inland, they excavated part of the ancient Greco-Roman city of Anthedon (fig. 10), one of the most important Hellenistic-era ports on the Mediterranean, which had been sought by archaeologists for generations. This site was ideal for excavation because it was a rare open space in the densely populated Gaza Strip. A series of emergency excavations were conducted by the Palestinian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities and Humbert’s team throughout the early 2000s in response to the intensification of the Israeli occupation and the site’s impending development.

In 2012, the Permanent Delegation of Palestine to UNESCO submitted Anthedon Harbour to its Tentative List—the first step towards nomination to the World Heritage List—citing its outstanding universal value as a “rich socio-cultural and socio-economic interchange between Europe and the Levant.” 13 The site is currently still on the Tentative List for Palestine. Although the World Heritage List and such national and universalising processes of listing can be understood as ‘a continuing project of colonization that places European values as central to human history’ 14, this designation can also provide much-needed resources, attention, and protection to historic sites.

Methodology

This is the first project in which FA has conducted an archaeological excavation using those same methodologies that we have designed to uncover human rights violations in urban areas.

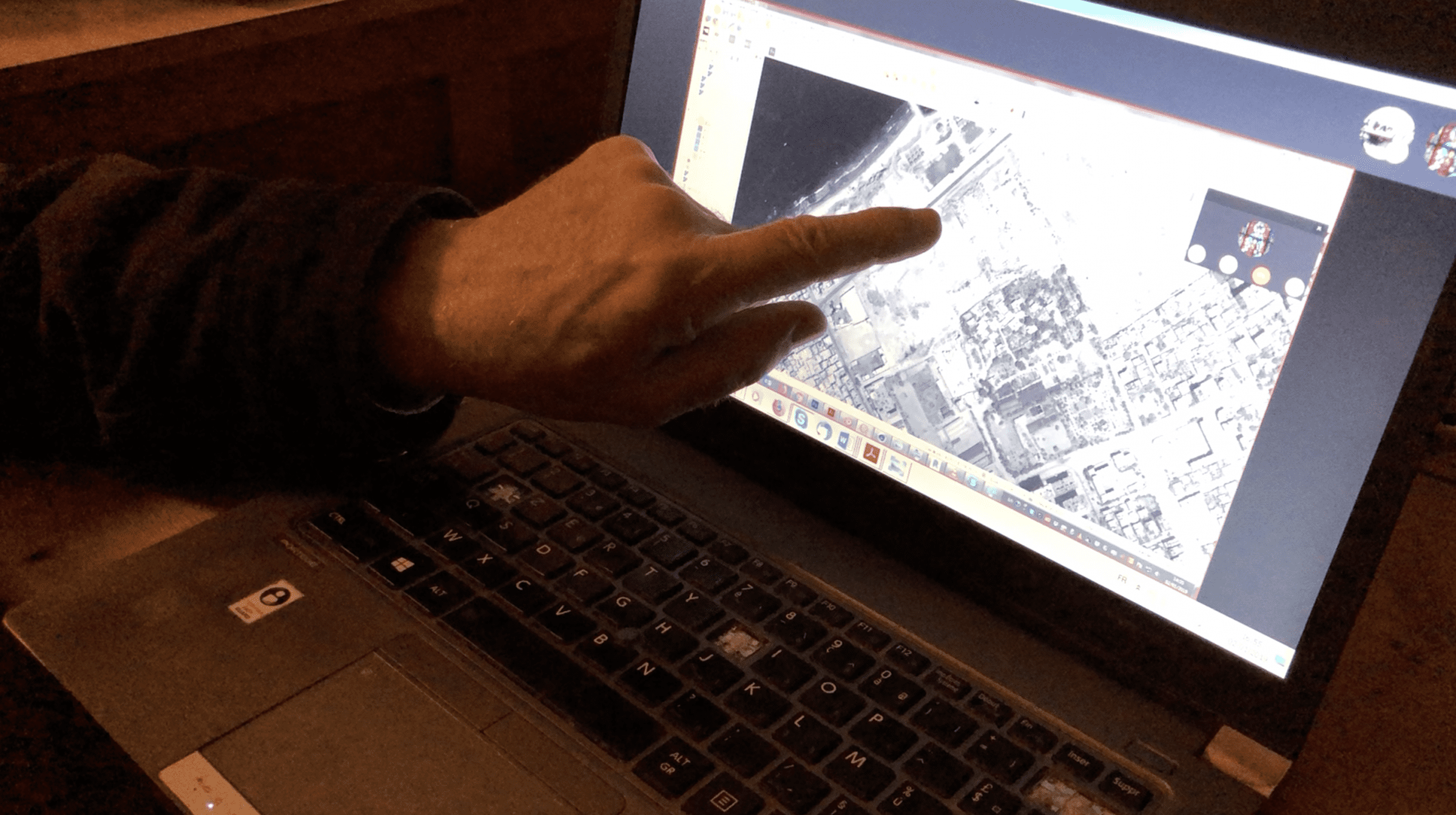

We worked with Humbert at the École Biblique, near the Old City of Jerusalem, to understand and locate the site and its elements. He shared with us archaeological reports 15, survey photographs, drawings (figs. 11 and 12), and a diagrammatic model of the Roman city built by his team at their office in Jerusalem (fig. 13), all of which helped us to accurately document the past in relation to the present reality on the ground.

In addition to the materials provided by Humbert, we searched the internet and social media (fig. 14) for further data about the site, including contemporary development and forms of use and the consequences of Israeli attacks.

We also worked with Palestinian and international journalists who provided us with information about the location of the site and photographs of the exposed ruins along the coastline (fig. 9).

FA began to map the full extent of the excavations undertaken by Humbert’s team, overlaying the main survey plan made by the archaeologists on a satellite image of contemporary Gaza (fig. 15). The scope of the archaeological remains—from the Byzantine-era cemetery in the north, to the Greco-Roman city of Anthedon, to the Iron Age defensive structures in the south—speaks to the city’s continuous importance as a site of cultural and economic exchange.

Our researcher met with residents and fishermen in Gaza who walked her through the exposed remnants at risk. Together with the Palestinian production organisation Ain Media, we also conducted original drone surveys (fig. 16) of the area, allowing us to recreate the coastline as a 3D point-cloud (fig. 17).

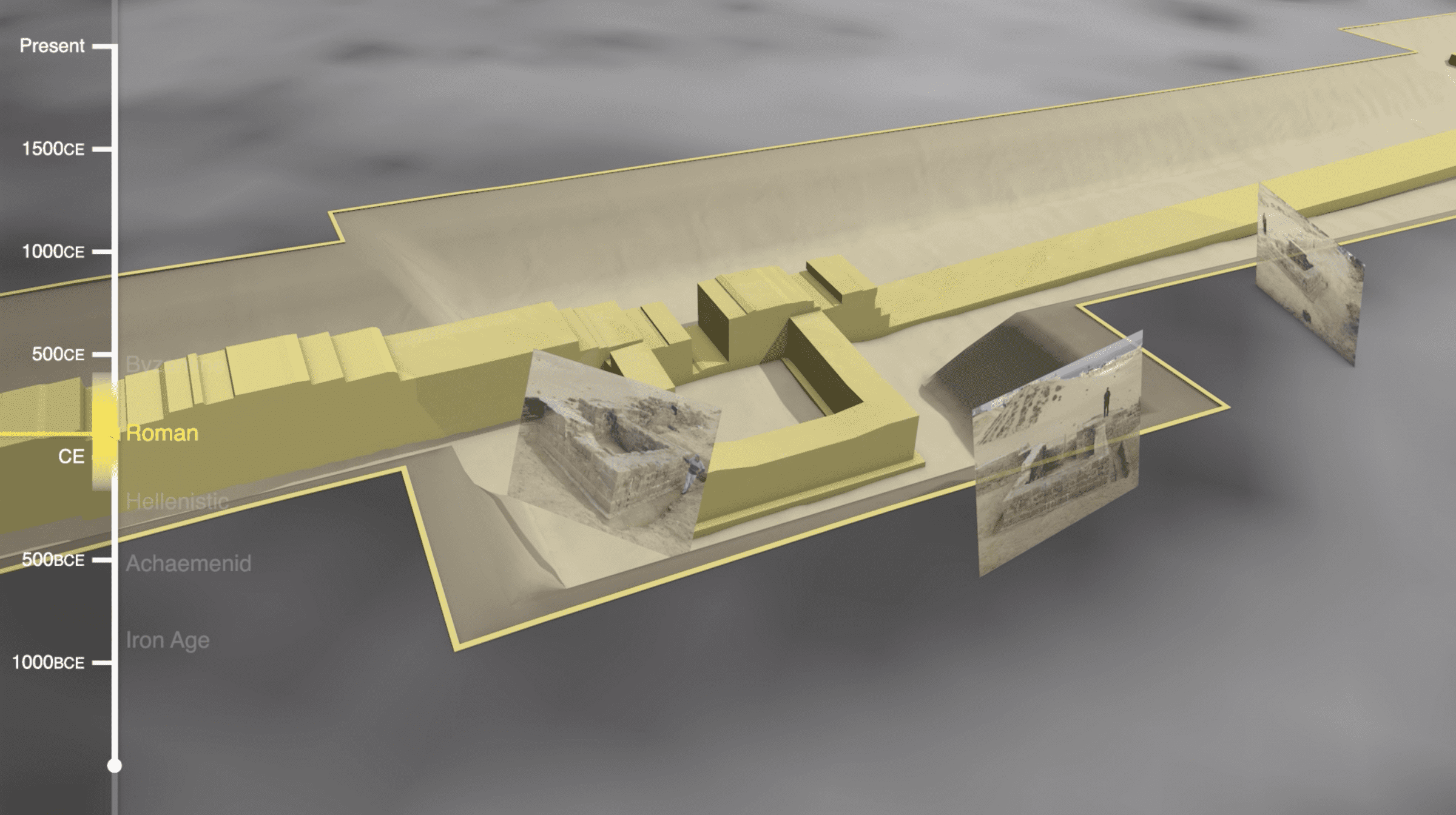

Since archaeologists have been restricted from accessing the site for almost a decade, and as these remnants were reburied by Humbert’s team for their protection and preservation, the relation between these many invaluable layers of Palestinian heritage can at present only be digitally reconstructed. Thus, using a unique combination of 3D modelling technology and image mapping, FA recreated each known historic structure using archival photographs and drawings (fig. 18).

Where traditional archaeology reconstructs the lived experience of people through their material remains, this form of open source archaeology opens up a vaster timeline that establishes the relation between each historical layer. Through this stratigraphic succession that extends from the ancient past to the contemporary present, we reveal a story of continuity of inhabitation.

Satellite image and crater analysis

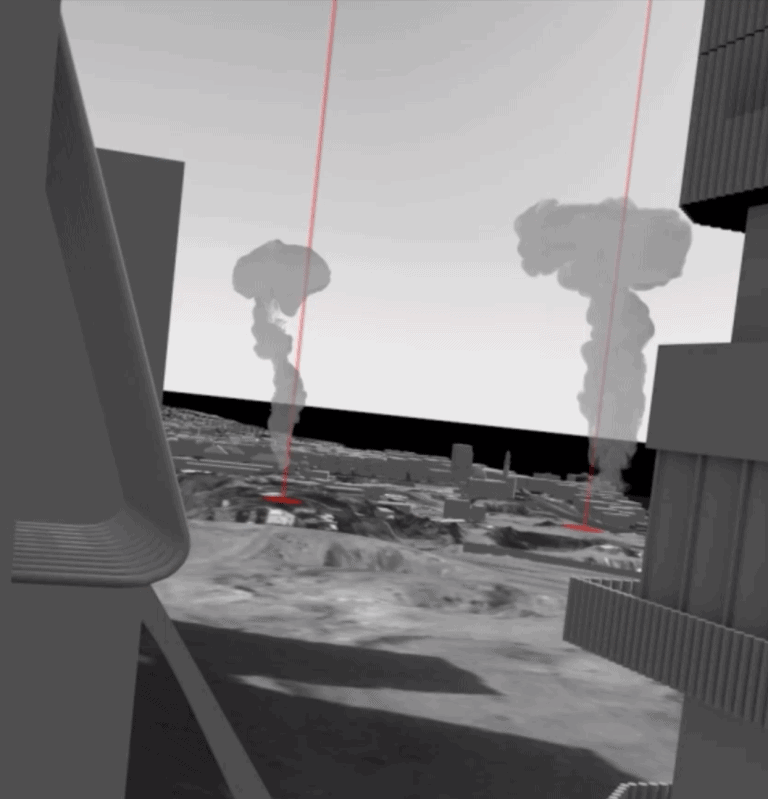

The smartphone clip pictured below (fig. 19), filmed by Palestinians during the 2018 Israeli military incursion, shows bombs landing on the surface above the site (fig. 20).

Our analysis of satellite images reveals many large craters caused by repeated Israeli bombings in 2012, 2014, 2018, and 2021 that have done progressive damage to the site (figs. 21-24).

Some of these craters are only metres away from key archaeological remnants or, in some cases, have been identified where we know these remnants to be located (fig. 8). While a Palestinian police station and a military facility take up parts of the known archaeological site, the bombs have also impacted remnants located near a mosque and residential area of the Al-Shati refugee camp, as well as along the coastline.

Development

Space is precious in Gaza. The Israeli occupation, resulting in overcrowding and poverty, as well as pressures inside Gaza, have necessitated the construction of essential technical and social infrastructure over known historic sites.

Emergency excavations of the Greco-Roman city were conducted from 2001-2005 to pre-empt the construction of a mosque and public sports facilities that have since been constructed on the margins of the site in order to serve the community of the Al-Shati refugee camp (fig. 25).

Coastal erosion

After winter storms, coins and pottery shards are often found in the sea or at the foot of these cliffs (fig. 16) under the Al-Shati refugee camp, where they are collected and sold by local fishermen. 16 This signifies rapidly advancing erosion that places precious archaeological remnants and coastal infrastructure at clear risk.

In 1995, Humbert and his team uncovered the above Roman water fountain (fig. 26) along the coast, which has a distinctive mosaic decoration that indicates people would gather here and draw fresh water. Over time, a complex network of pipes has been built through the site. The construction of these pipes and resulting runoff, combined with coastal erosion, has exposed and damaged these ruins.

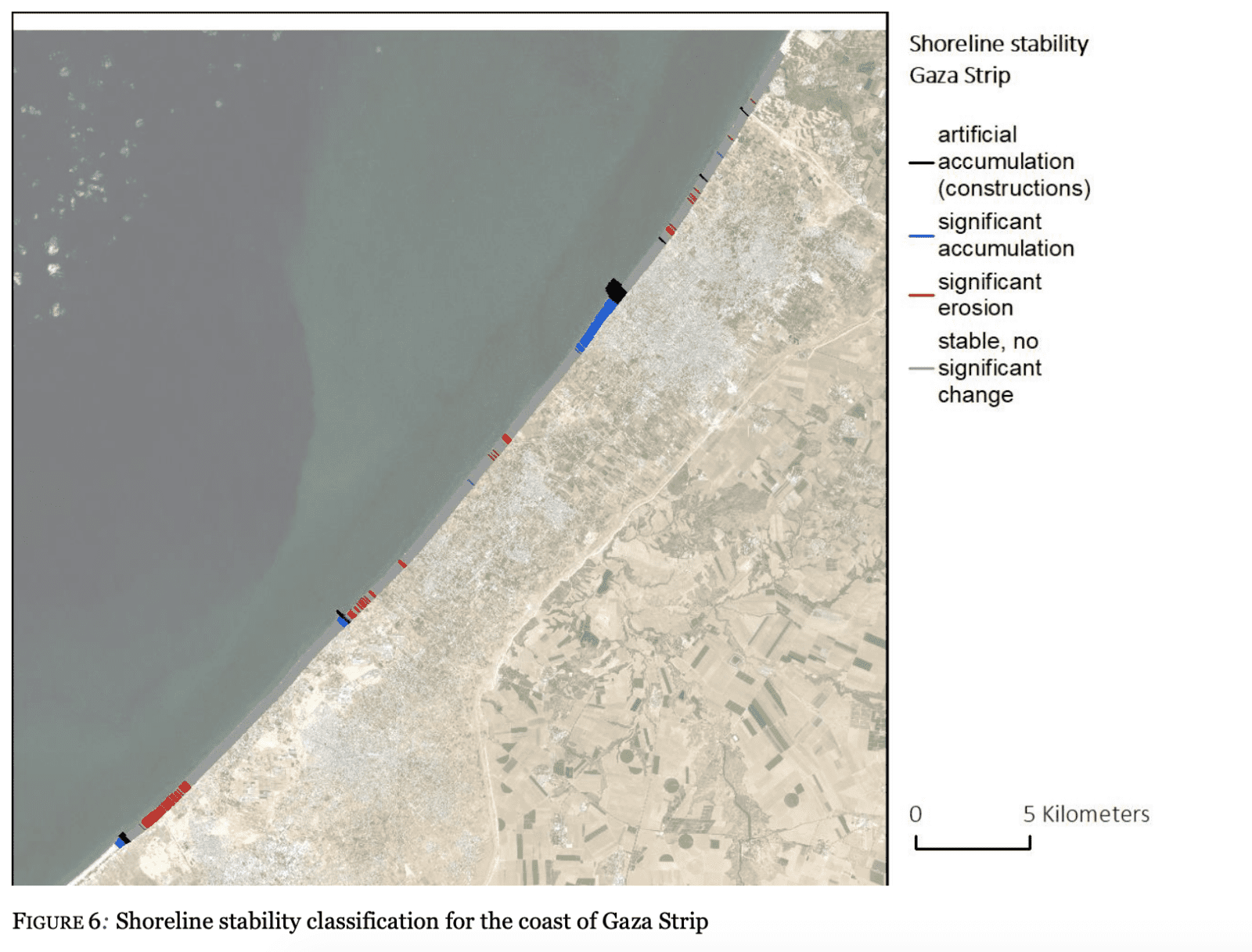

A study of shoreline mapping in the Gaza Strip from 1995-2020—conducted by the EO Clinic of the European Space Agency (ESA), in partnership with the UNDP Gaza Office—shows that construction along the coastline disrupts sea currents and has led to patterns of accumulation and erosion, yet another urgent threat to the livelihood and property of its inhabitants. 17 In this study, the stretch of coastline where our site is located is classed as having undergone ‘significant erosion’, meaning the shoreline has reduced by at least 10 metres since 1995 (fig. 27).

Legal analysis

The above-mentioned independent legal report by Al-Haq, which builds from this investigation, demonstrates the ways in which Israel’s differential treatment of archaeology—the disregard and destruction of Palestinian heritage, versus the preservation of archaeological sites under its territorial control—is a key component of Israeli apartheid. 18

In their report, Al-Haq outlines the ways in which ‘the targeting of Palestinian cultural heritage, fundamentally affects the core of their identity and existence as a people’ 19. The report goes on to explain that ’Israel sets up two distinct standards tailored upon their added value to the entrenchment of the Zionist narrative over Palestinian lands. On one hand, cultural heritage sites that serve this narrative and are directly controllable by the Israeli Occupying Forces are appropriated and exploited to reinforce this narrative. On the other hand, cultural heritage sites that conflict with this narrative are, straightforwardly or not, targeted, damaged and destroyed, in an attempt to erase them from memory.’ 20

In addition to the crime against humanity of apartheid, Al-Haq argues that Israel’s attacks on cultural property in Gaza amount to war crimes, especially as these are committed as part of a widespread, disproportionate, and systematic attack against the civilian population. 21

Al-Haq and Forensic Architecture call on The Prosecutor of the ICC to consider this destruction as amounting to war crimes, and to evaluate their potential contribution to apartheid as a crime against humanity under the Rome Statute. 22

References

1 The time periods are approximately understood as follows: Iron Age (1200–539 BCE), Achaemenid (539–330 BCE), Hellenstic (330–31 BCE), Roman (31 BCE – 634 CE), Byzantine (390–636 CE).

2 Nur Masalha, The Zionist Bible: Biblical Precedent, Colonialism and the Erasure of Memory (Routledge, 2013).

3 Nadia Abu El-Haj, Facts on the Ground (London: The University of Chicago Press, 2001).

4 State of Palestine Ministry of Tourism & Antiquities, Report on The Israeli Occupying Power recent violations in the World Heritage Property “Hebron/Al-Khalil Old Town” (Bethlehem, 26 December 2019).

5 Al-Haq, Cultural Apartheid: Israel’s Erasure of Palestinian Heritage in Gaza, 23 February 2022.

6 United Nations General Assembly, Human Rights Council, Resolution adopted by the Human Rights Council on 22 March 2018: 37/17 Cultural rights and the protection of cultural heritage (9 April 2018).

7 United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), ‘Protection of Civilians Report | 24-31 May 2021’, Protection of Civilians, 4 June 2021.

8 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (Article 8, pp.4-5).

9 Fatou Bensouda, ‘Statement of ICC Prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, respecting an investigation of the Situation in Palestine’, International Criminal Court, 3 March 2021.

10 The Office of the Prosecutor, International Criminal Court, Policy on Cultural Heritage, June 2021 (p.10).

11 Al-Haq, Cultural Apartheid: Israel’s Erasure of Palestinian Heritage in Gaza, 23 February 2022 (p.8).

12 Fareed Armaly, ‘Crossroads and Contexts: Interviews on Archaeology in Gaza. Fareed Armaly with Marc-Andre Haldimann, Jawdat Khoudary, Jean-Baptiste Humbert, and Moain Sadeq’, Journal of Palestinian Studies, 37.2, Issue 146 (Winter 2008), pp.43-82.

13 UNESCO, ‘Anthedon Harbour’, UNESCO World Heritage Convention: Tentative Lists, 2 April 2012.

14 Laurajane Smith, ‘Discussion’ in Heritage Regimes and the State,

ed. Regina F. Bendix, Aditya Eggert, and Arnika Peselmann (Göttingen: Göttingen University Press, 2013), pp.389-395.

15 Ministère Palestinien du Tourisme et des Antiquités, Ministère Français des Affaires Étrangères and École Biblique et Archéologique Française de Jérusalem, Mission Archéologique de Gaza: Coopération Franco-Palestinienne 1995-2005 (Ecole biblique et archéologique de Jérusalem, October 2012).

16 BBC News Arabic, ‘Treasure Hunters‘, BBC News, 24 January 2020.

17 EO Clinic (at the request of the UNDP Gaza Office), Shoreline Mapping in the Gaza Strip, 29 September 2020.

18 Al-Haq, Cultural Apartheid: Israel’s Erasure of Palestinian Heritage in Gaza, 23 February 2022.

19 Ibid., p.21.

20 Ibid., p.23.

21 Ibid., pp.19-21.

22 Ibid., pp.23-24.

Update

09.03.2022

09.03.2022

On 9 March, Al-Haq on behalf of partner organisations delivered an oral statement under interactive dialogue with UN Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights, as part of its engagement with the Human Rights Council 49th Session. Building on Al-Haq’s report, the statement addressed Israel’s apartheid policies and practices targeting Palestinian people’s cultural rights, particularly Israel’s bombardment of cultural heritage sites in the Gaza Strip during its May 2021 military offensive.

Update

19.12.2023

19.12.2023

This important archaeological site—already under threat from previous Israeli bombings and siege as detailed above—has now been mostly destroyed in the Israeli invasion of Gaza.

The present destruction of the site by the Israeli occupation forces has unfolded in three stages: (1) airstrikes, (2) surface-level demolition, and now (3) the installation of water pumps ostensibly to flood underground tunnels.

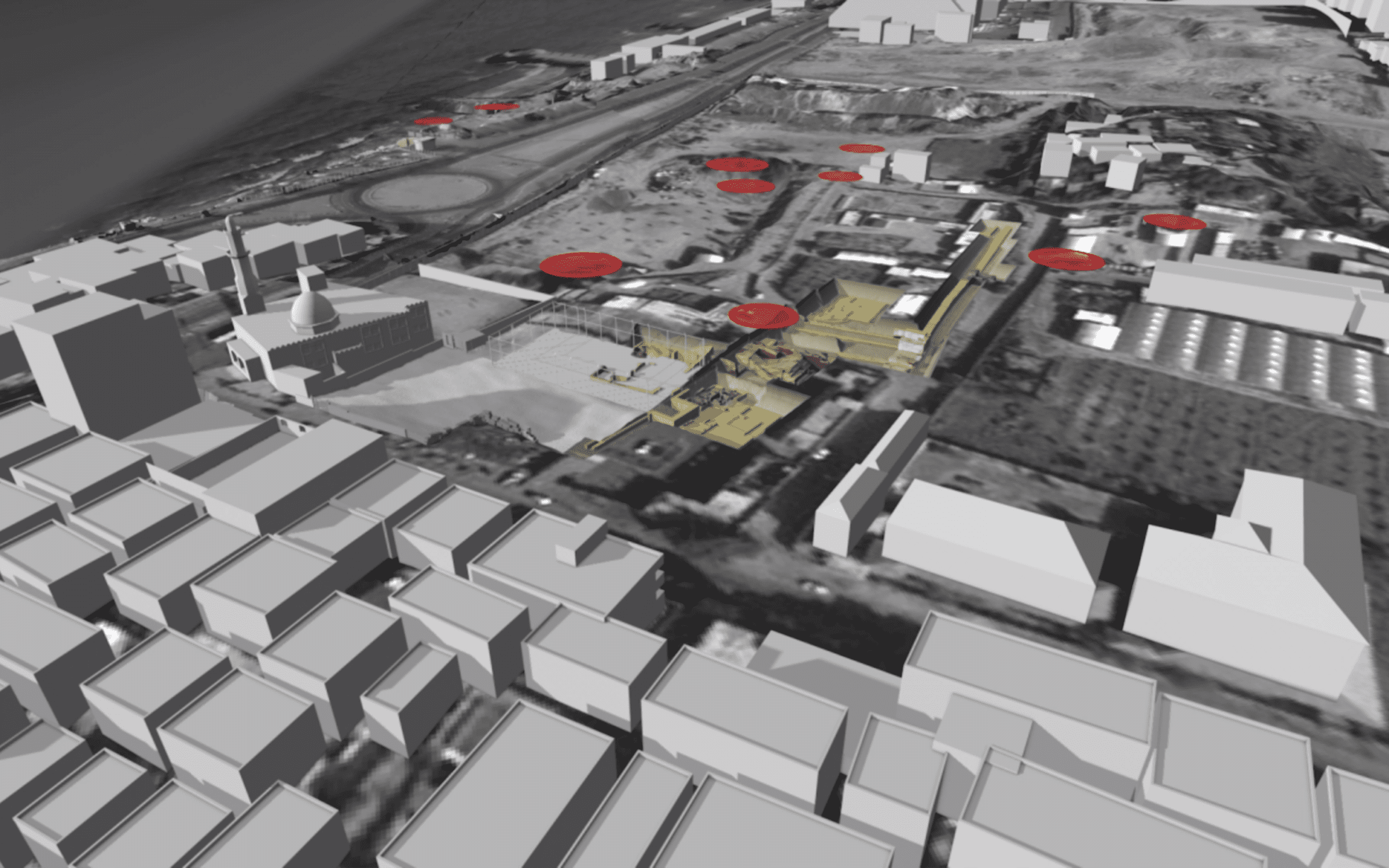

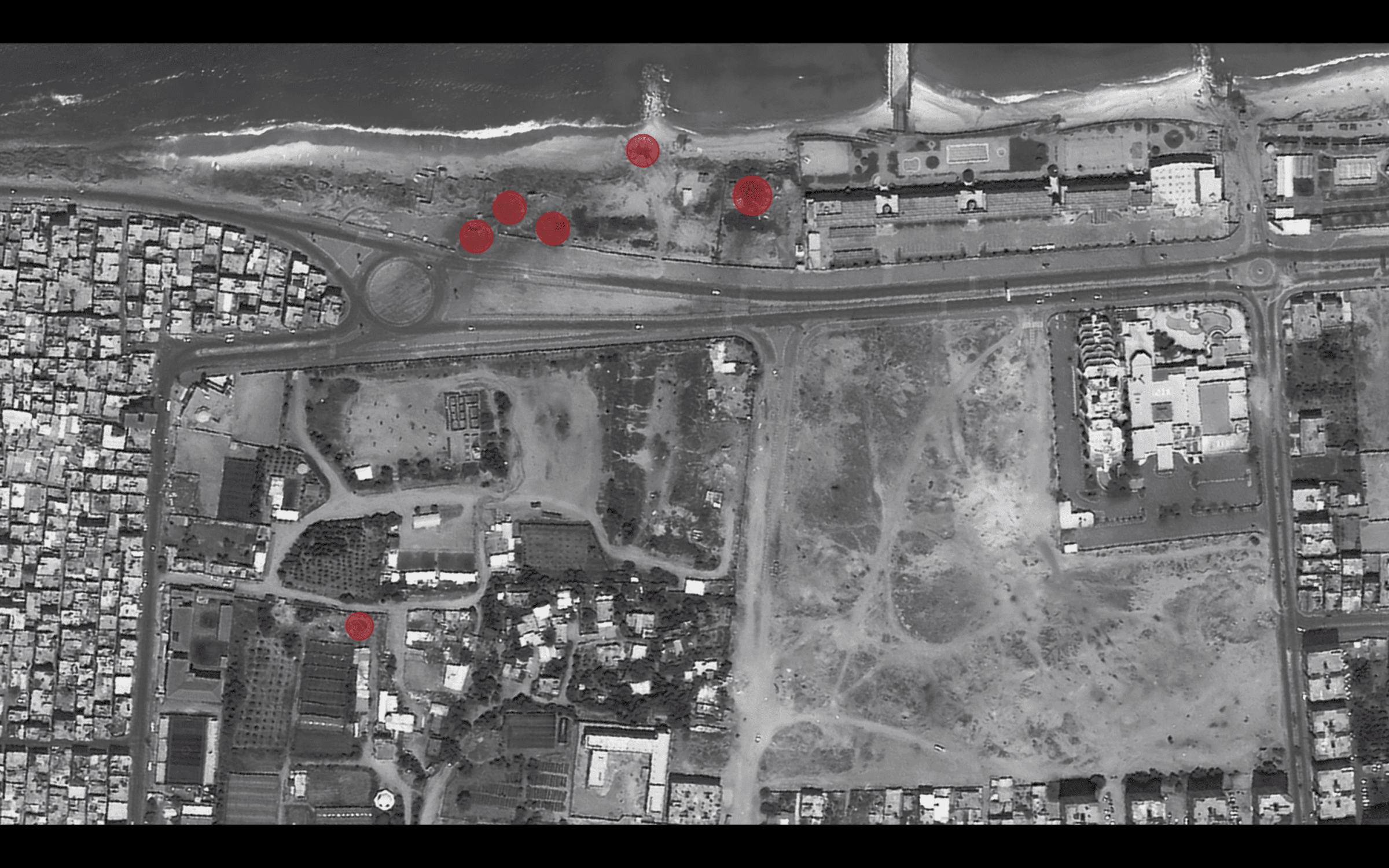

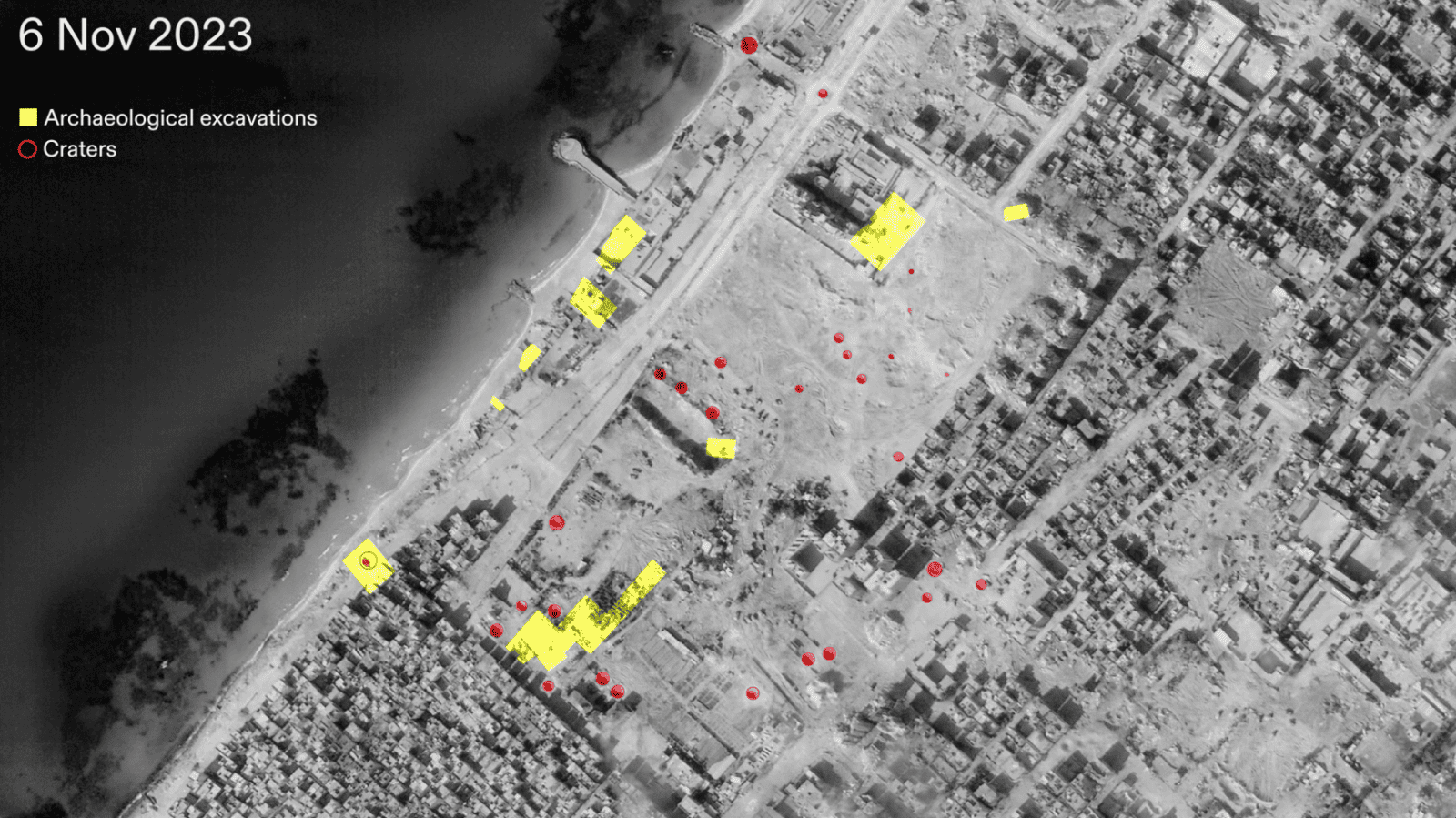

Satellite imagery shows that between 8 October 2023 and the beginning of the Israeli ground invasion in November, the archaeological site was riddled with dozens of craters from airdropped munitions. By 6 November 2023, we can identify more than thirty craters (marked in red) across the area, ranging in size from 8–16 meters in diameter (fig. 28).

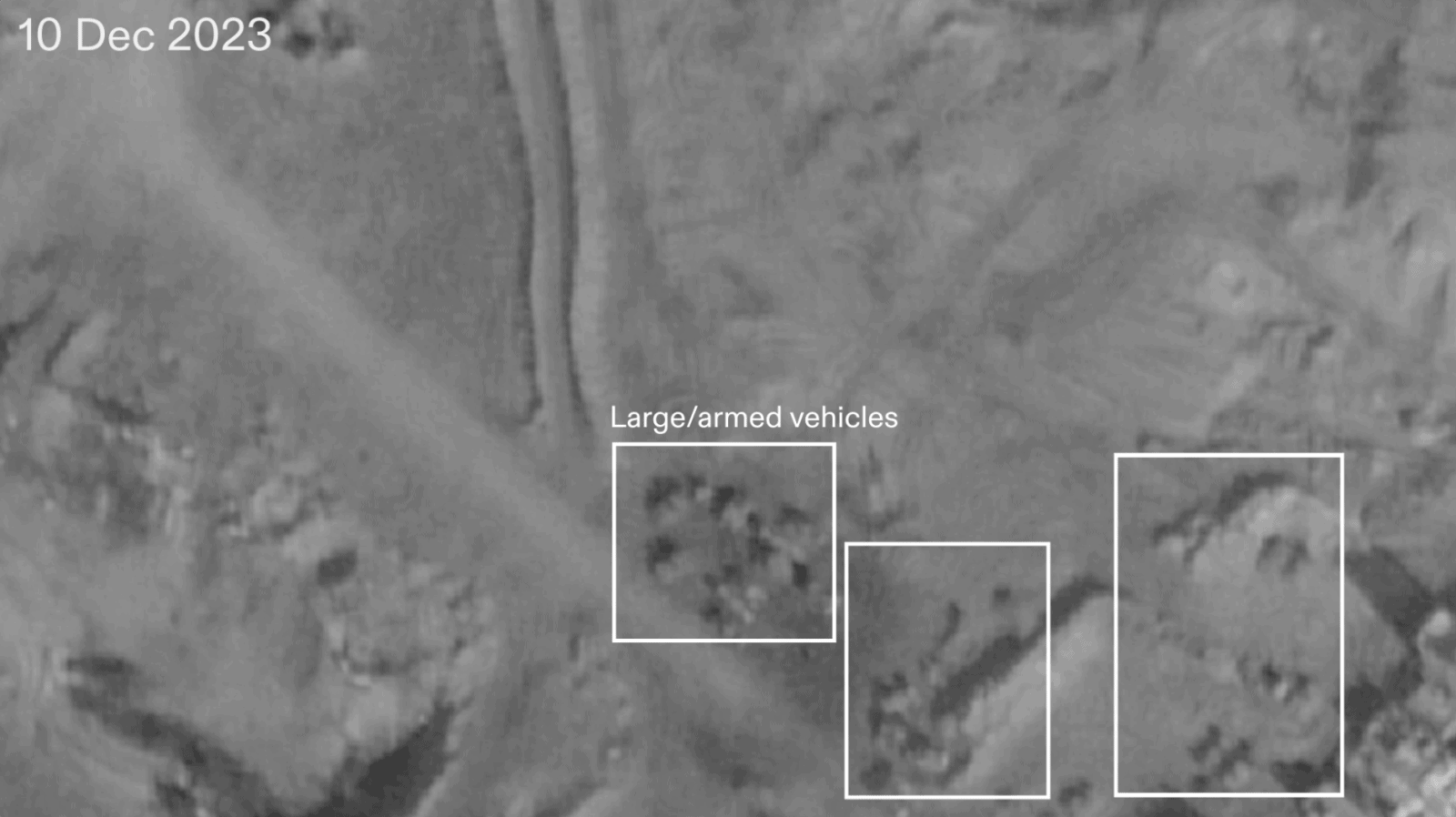

Following the ground invasion, large vehicles (likely military bulldozers and tanks) were used to terraform the area, turning the site into what appears to be a military outpost. In satellite imagery from 10 December 2023, over 35 vehicles are identifiable, and many are armed (fig. 29).

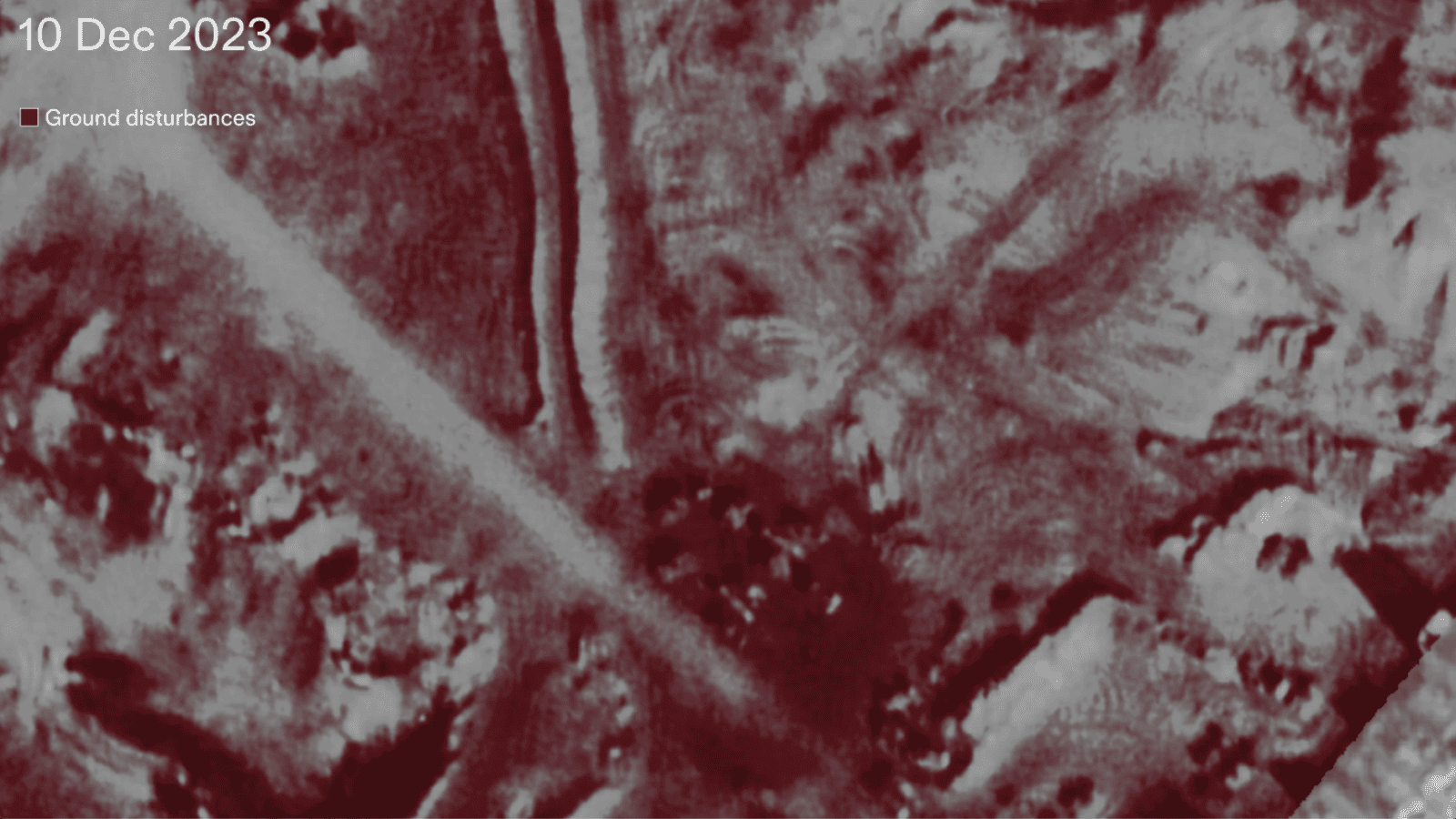

We used remote sensing to register ground disturbances and areas of change since 8 October 2023 (fig. 30). The earth, ravaged and overturned by Israeli military vehicles, likely contains damaged archaeological remnants and artefacts that were previously lying below the surface.

On 13 December 2023, the IOF reportedly began flooding tunnels under Gaza with seawater. Environmentalists caution this destructive act will render Gaza uninhabitable by compromising its already limited groundwater for several generations to come.

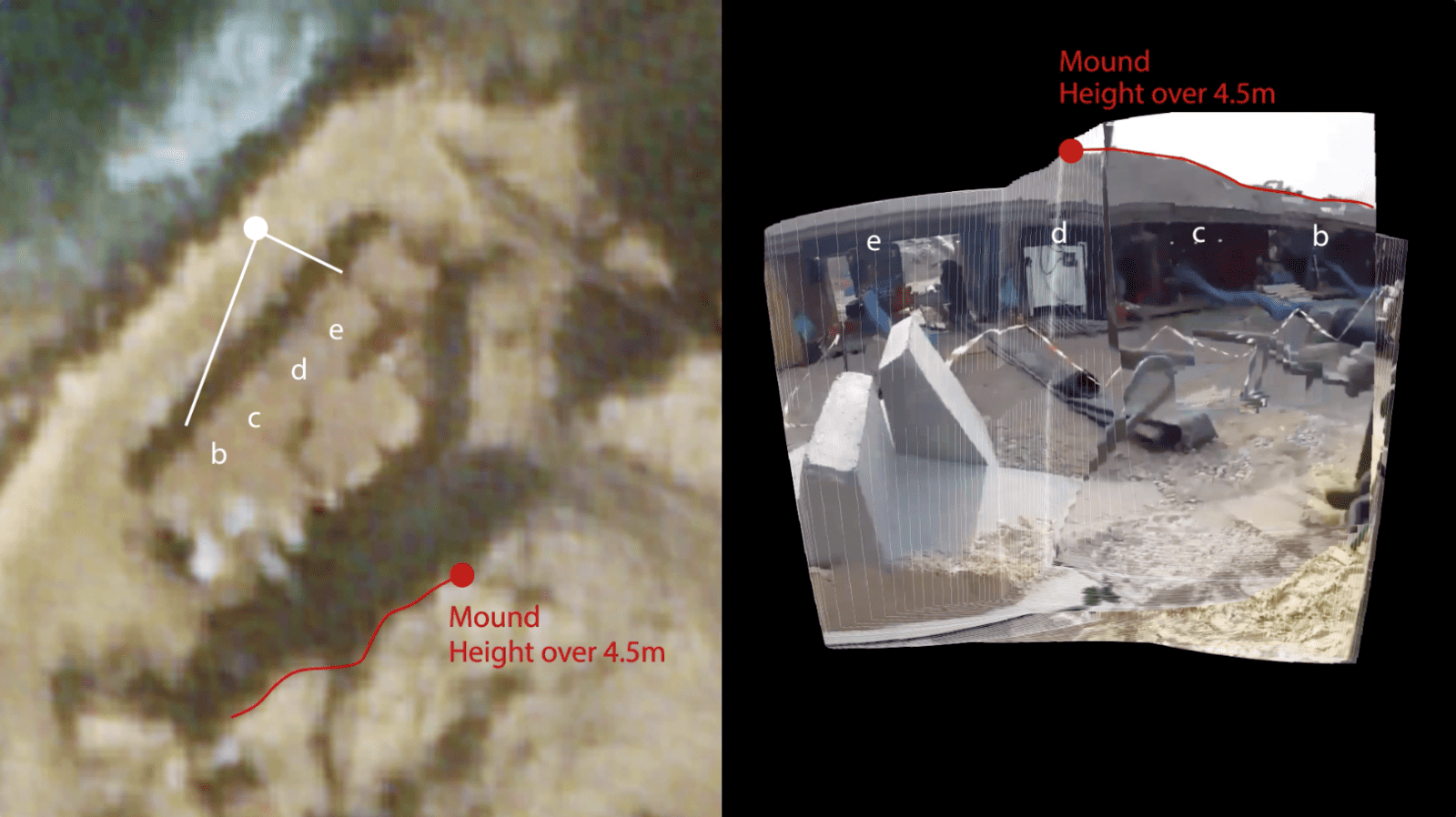

Satellite imagery from 8 October – 10 December 2023 reveals the development of Israeli water pump infrastructure in and around the archaeological site. Early signs of the construction of these pumps can be registered in a satellite image dated 14 November 2023 (fig. 31). Additionally, we identified pipes and an earth mound at least 4.5 meters in height in a ground-level video posted by the Israeli occupation forces on 6 December 2023, labelled with a biblical quote ‘and the water will return’ (fig. 32).

In a report accompanying our updated findings, Al-Haq links Israel’s destruction of Palestinian cultural heritage to the environmental damage caused by pumping seawater, which constitutes ‘unambiguous evidence of Israeli officials and military’s intent to erase and destroy the Palestinian people in Gaza’.

Al-Haq elaborates that ‘this destruction of Gaza’s rich cultural heritage, which occurs alongside the large-scale killing of Palestinians, significantly testifies to Israeli officials and military commanders’ intent to destroy the Palestinian people as well as erasing their identity… flooding the tunnels of Gaza, with the knowledge of the devastating short and long-term consequences experts have warned of, is a deliberate attempt to deprive resources indispensable for the survival of the Palestinian people in Gaza…’.

Al-Haq goes on to analyse Israel’s destructive military actions in light of international law, concluding that the destruction of cultural heritage and damage to the environment in and around this important archaeological site amounts to genocidal intent under the United Nation’s Genocide Convention, The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), and case law of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY). Al-Haq calls on Third States to take concrete and effective measures to prevent the flooding of Gaza’s tunnels and enforce an immediate ceasefire and to ‘act in line with their obligations under the Genocide Convention, including by unilaterally and collectively taking all feasible action to urgently and definitively ensure an immediate end to the ongoing atrocities, and that Israel refrains from the perpetration of conduct prohibited under Article II of the Convention.’